Shelley Lake was interviewed at her studio in western Massachusetts on a lovely sunny summer day in June 2006. Her website can be found at www.shelleylake.com

MAGNAchrom: As an artist are you known as DOCTOR Shelley Lake?

Shelley Lake: Some people refer to me that way jokingly, but for the most part they call me Shelley.

MC You’ve been in the arts most of your life. As a child were you artistically-driven?

SL I started when I was three and have thought of myself as an artist all my life. Even when I was practicing chiropractic, I thought of it as a tactile art.

MC And as a three year old child, how do you know you are an artist at that point?

SL Well, I got a lot of support and affirmation early on doing crayon drawings — particularly drawing very early and I still draw quite a bit and enjoy using my hands to create art even though I interface with technology I still maintain hand skills as much as possible.

MC So if you have a tactile need for art, and it’s clearly coming out in chiropractic as in art, how does photography satisfy you?

SL Well, that’s a good question...

MC Is it all the gear? I mean, (laughing) there is a LOT of stuff to touch and move and so on — is there a technical aspect to it?

SL I think I was looking for a creative partner, which has been a theme in my adult life as I move away from the more direct ways of making art to more technically-oriented art making. I found that working with the camera enabled me to capture places instantaneously that would otherwise never be envisioned.

MC Is it more of a personal thing? You seem driven to capture pictures that have a sense of “being there” and clearly you need to capture that somehow for yourself. Thus, in terms of commercial work, are people coming along for the ride? Are they following your work like a person would follow a movie, a cinema?

SL The camera enables me to revisit places that I can only experience briefly. Some of these places are so expansive that even though you are standing there, you can’t witness them except by revisiting them through the camera. I’ve often said that the camera is just an excuse to go to beautiful places. For a while I went to these places and never thought of bringing a camera because I felt that they couldn’t be captured. And it is only recently that I decided that I would try anyway.

MC And it seems that you have done it. That you have captured “something”...

SL it is an approximation of the place and it’s not as good as being there, but it is the best I can do.

MC But you’re also capturing the “feel” — I mean, looking around here in your studio there is a drama here in all of these pieces. Are you a dramatic person?

SL No. But I’m drawn to (laughs) dramatic people! (pauses) And I’m drawn to dramatic places with a tremendous sense of scale. I’m often at the edge of some precipice in order to do these captures. Sometimes it is frightening to just stand there with my camera ‘cause I’m often cliff-side. That’s pretty dramatic.

MC You don’t have any phobias about heights or anything?

SL No I don’t. But there are many times when I’m literally on the edge and am concerned for my life.

MC A wind might take you away...

SL Or the ground might give way, ‘cause some of the erosion is really bad and I know that a lot of people have stood where I’m standing. I see all the tripod marks. There are definitely moments when I’m concerned about my safety.

MC Well, speaking of moments, can you tell us the worst thing that has ever happened to you while you were taking pictures?

SL (laughs) Well, I accidentally lost a rig at Horseshoe Bend and ended up losing a 4x5 camera and the BetterLight panorama option over a cliff. But fortunately the digital back (the insert) was tethered to my backpack so at least I didn’t lose the back. And the back actually wacked against the cliff-side and I was able to fish that out. The back still works perfectly.

MC So it didn’t need to be repaired?

SL No.

MC What about the camera?

SL I ended up hiring a river guide and going back into the canyon at Horseshoe Bend to retrieve the remains. And I still have bits and pieces of the camera. I thought that the insurance would honor my policy if I had the remains, but that really didn’t end up being that important. It was more that I really wanted to see what happened to it.

MC I see. And the lens of course, was gone, gone, gone...

SL Yeah, but I actually recovered half of the lens! And I also recovered the panorama option and sent it back to BetterLight.

MC So if that was the worse experience — just an equipment thing — then what was the best experience?

SL The best thing, hmmm... You wonder what makes something the best. There have been moments in the field that were extraordinary with the camera. Sometimes it involved waiting, sometimes it was sheer luck. And luck seems to be a big part of the process — as someone who is totally out of control (laughs). Part of moving into photography was control. It affords a tremendous amount of control. Maybe not as much as simulation-based graphics, but close to it. Yet you are at the mercy of the elements and the weather and the wind.

MC Is there a hint of gambling in there? Or is that just more of a spiritual thing? Because you must be unlucky sometimes too...

SL Oh yes, Most shots are absolute failures and I have plenty of those... I find with the BetterLight back I almost always have one or two opportunities in a capture. It’s not like I can bang out a dozen shots at a site. So it’s usually a singular experience with the camera.

MC Perhaps no different than using an 8x10? I mean, it’s the same situation: with getting only one or two shots in.

SL Yeah that’s right.

MC Does that make the luck sweeter then? Because of the limitations?

SL Yeah I think the limitations are great, but because of the resolution and color fidelity of the back, the odds are really good that the capture will go well. And then it becomes a matter of composition and timing.

MC For such panoramic shots, you must have to do quite a bit of “pre-visualization” because you really don’t have the time to run through the whole scan, look at it, modify your composition, and then go back.

SL That’s exactly right.

MC You gotta just look at the scene and say “I think this is going to look good”...

SL Yes absolutely, that’s true. With panorama I use the laptop to visualize the composition, instead of the groundglass. I typically overshoot the scene spatially so that I have some wiggle room.

MC Mostly in the horizontal direction?

SL And some top and bottom. Often but not much. I’ve had a lot of success stitching shots together even though I have the panorama option. The focus is totally unforgiving. So that is a critical part of the equation

MC And you use the software to do that?

SL No, I typically use a loupe on the groundglass. In the field I don’t use the auto-focus feature of the back. To me it’s too risky. And I often don’t have time to pursue that.

MC Right. It slows you down — one more step.

SL That’s something I would use in the studio religiously but not in the field

MC You also shoot with a Fuji 617. Can you compare the WAY you approach your subject with that camera versus the bigger BetterLight equipment?

SL I think of the Fuji medium format camera as a “point and shoot” camera even though it’s unwieldy in some circles compared to the 4x5 platform. It’s extremely convenient and spontaneous. So it affords the spontaneity that I otherwise can’t enjoy with the 4x5 platform. Using it compositionally is much more straightforward because the rangefinder approximates the shot instantly whereas the panorama option is much more mysterious as to what the outcome will be. It’s funny with the medium format: I tend to “bulls eye” my shots more than with the panorama option. Not sure why that is.

MC What do you mean by “bulls eye”?

SL Where the focal point is in the center of the shot.

MC So more “formal” then?

SL Yeah, I tend to be more sprawling with the panorama option.

MC It’s interesting. I see that now, with the exception of that piece that they have an asymmetry to them which is very appealing.

SL I think so too. I’m less likely to bulls eye with that panorama option. In the medium format, I’m also able to do verticals which I’ve begun to explore. That’s a refreshing change from the horizontal format.

MC I haven’t seen your verticals!

SL I don’t do them often, but I’m beginning to explore them more.

MC If you were traveling today with the BetterLight, would you be bringing your Fuji with you as a companion camera?

SL Yes, and I have done that. When I’m on photo safari in my RV I bring everything. Even the Canon 1Ds digital.

MC So you basically have a complete toolkit. Is that a problem? You suddenly have all these choices!

SL No. I like having choices. And I’m not intimidated by choice. The more familiar I am with each platform, the easier it is for me to make the choice. That was true even in massage modalities ‘cause I would learn shiatsu and chiropractic and Swedish and a multitude of things and the more familiar I became with each modality, the easier it was to make a choice.

MC Back to that tactile thing: it’s becoming one with your equipment so that you can become one with your image, is that right?

SL Yes.

MC Is that why you have to be the best in a platform, get to really learn it, and then you won’t get rid of it? It’s almost like being married for a while.

SL That’s true. For the first year I only used one lens with the scanning back — I used the Schneider 90mm XL. And it was a good exercise. Having only one lens and no other choice. And I became very intimate with that lens and wasn’t distracted. I think sometimes it’s good to constrain the situation just to master something well enough to move on to the next experiment.

MC Do you think those photographs where you limited yourself are more intimate than your later work?

SL It’s more like an evolution as I introduced new elements into the toolkit, I’m able to optimize each element for each situation. And it’s often an optimization experience where one combination is going to yield the most beautiful result. And the same thing is true in Photoshop — you have levels, curves, color balance, selective color, and a gazillion choices. Knowing that hue/saturation is the appropriate tool for this problem set versus selective color. Those nuances make a huge difference. And you can only realize those skills by mastering one tool at a time.

MC Did you have formal darkroom training?

SL Yes. I started when I was 13 in the darkroom in the closet making prints with an enlarger and chemicals.

MC Personally, I find that wet background the perfect analog to Photoshop as a darkroom. And yet there are things you can clearly do in Photoshop that would have taken you bloody forever to ever try to attempt in the darkroom! For example, something simple like wanting to warm up the shadows — and nothing else. It’s trivial to do in Photoshop yet painful to do in a wet darkroom.

SL Right. Photoshop is the state of the art in software engineering. Everything pales in comparison.

MC When did you first start using Photoshop?

SL I guess I started with Macintosh in the mid 80s.

MC Did you use MacPaint, MacDraw?

SL Yes, I have an early example of that on my website. I did a capture of the early Mac user interface and created a billboard-sized print as art.

MC You were at MIT at the time?

SL I was at MIT from 1977 through 1979. That’s why it’s such a blur for some of the dates ‘cause I had exposure to Photoshop-like environments a decade before they became commercially available.

MC So tell me about MIT. In particular how this MIT experience has lent itself to your ability as an artist today.

SL The most important thing I learned at MIT -- and it’s still important today -- is: does it feel good? That was the foundation from which everything grew. And that was Nicholas Negroponte’s vision for the computer interface. So it was a lot about feelings.

MC This was the “Visible Language Workshop”?

SL He called it the Architecture Machine Group back then. And now it’s the Media Lab. He let go of his involvement/control recently at the Media Lab.

MC He was one business man.

SL It always was a business. And it was supported by DARPA. All this technology was born of the military with the toolkits being staged on the field for military maneuvers.

MC I remember seeing in the early 80s an interactive 3-D map of Aspen.

SL Yes it started with Aspen. They took a car and put four cameras on top of it looking north/south/east/west and captured every meter of town and all the menus and was able to gather enough data about Aspen so that you could visit Aspen vicariously through the computer.

MC Hah! Woefully out of date today! You wouldn’t recognize the place! (laughs)

SL Yeah isn’t that funny? There was a project that pre-dated Aspen that I was personally involved in which was the first art-slide videodisk. We digitized every slide in the Roche library (MIT) so that you could go to that library online, interactively.So it was the first project of its kind and it pioneered the interactive video disk.

MC That issue of the underlying military connection — you had no problem with that because that was just where the money was coming from?

SL I guess if the military is going to invest money in a pursuit, I can’t think of a better way to spend it. It was peacetime more or less and it was an inspiring and peaceful experience to be in the laboratories. Even though the technologies could be used or repurposed for anything. And that is the nature of technology — it has the potential for good or evil. But it is the people behind it that ultimately determine its fate.

MC That’s true of art as well. The technology has nothing to do with whether a photograph is digital or analog. Do you get into the debate about film vs. digital? Or do you try to stay away from that?

SL Ironically I just bought a film camera on the heels of this digital revolution and find that film as a platform is still solid, and has some timeless qualities about it, particularly for large format printing. And the two coexist side by side each having different strengths and weaknesses. I hope to see film... well to be honest with you, on some levels I wouldn’t mind if film went the way of the dinosaurs, because it is so counter-intuitive working with it often.

MC Isn’t that part of the joy of luck? That counter-intuitive, unknown, throw your dice and hope it comes back, and when it does it’s joyful?

SL (laughs)

MC Digital gets rid of some of that luck, don’t you think?

SL Oh no. The only advantage digital has is instantaneous gratification, instant feedback

MC Is that a good thing? Or bad thing?

SL It can be deceiving. Sometimes the small digital display when explored at a larger scale, may fall apart, or you may think you “got it” but you didn’t.

MC Is it because it encourages you to be lazy? As opposed to film, which bites you if you get lazy! You can get away with more stuff with digital...

SL (laughs) I’d say the scanning back is anything but lazy!

MC Of course! I meant more like your Canon 1Ds

SL The 1Ds MkII, in certain circumstances, does begin to rival the medium format platform for resolution and color fidelity. And its just a matter of time when things reach the 20-something megapixel range where we’ll see a turning point. But I think its so much more spontaneous. Particularly for the human form and portraits, where medium and large format really gets in the way of the human that’s doing portraiture.

MC Sure. Yet people still love shooting 4x5 portraiture, ‘cause there is certain look to it. And then there are others who go out and buy LensBabies on their teeny digicams to make it look like it was taken with a big format camera! For me it’s wacky to see these reactions more than anything.

SL Yes. As a teenager I loved photographing people. Now I’m a reluctant portrait artist. So I prefer photographing sculpture at this point (points to a framed photo of a detail of David)

MC I assume that is Florence at night?

SL Yes. That is David at the Palazzo Vecchio. The replica.

MC Taken with the 1Ds?

SL Yes

MC Yeah, you probably wouldn’t want to haul all your gear around at night and half an hour later you’d get your shot of David.

SL Actually, I’m ready to bring my 4x5 to Florence. I’d love to do that! I was scouting locations primarily so that I could later go back with the BetterLight.

MC That’s interesting. I think you and I have come to a similar conclusion, which is the use of digital cameras as a scouting tool. A digital Polaroid if you’d like. The pictures are good in their own right, But this allows me to come back later with a laser focus to get the ONE picture.

SL Absolutely. But I have to add that the Canon does a pretty good job. But I know that the BetterLight scanning back would blow it away.

MC So if today you had a Hasselblad H2 with a 39 megapixel digital back, would that change your camera makeup? Might you use one camera for everything?

SL Perhaps. I have not had that experience that you are describing to know how I feel about it.

MC Well, let’s go on to the future. You’ve had a varied artistic past, which includes everything from digital art to hands on art to analog photography art now traditional photography. Where do you see yourself as an artist in 5 to 10 years? Are you still going to be doing photography? 3-dimensional? Film? Where might you take those?

SL Well I’d like to return to simulation-based graphics. And I think in about 5 years that will be a lot easier to facilitate. I like the motion picture arts and sound and may explore some audio/visual multi-media projects.

MC More of an installation kind of thing?

SL Perhaps. As these LCD and plasma displays get cheaper... Last time I went to Chelsea I must have seen half a dozen installations that were motion picture based arts. And some of them were audio visual. It’d be great to have an electronic display instead of something on paper that’s more kinetic.

MC What will that do to photography when you can buy an electronic display — that size hanging on your wall — and subscribe to “Shelley Lake du Jour”? Is this going to be a business model? Is it going to make photography more ephemeral than it already is?

SL The idea of static furniture, although it is appealing to some people, something more idiosyncratic and kinetic would be interesting. You would always have the option if you’d like something to remain unchanged.

MC Perhaps it’s not that you’d hang electronic paintings on the wall, but rather that the walls would be electronic?

SL Absolutely, I’d expect to see that more or less as screens become more affordable and larger — floor to ceiling wall displays. The irony is that this is exactly what was going on back at MIT in 1977. I witnessed that early on knowing it was just a matter of economics and time before...

MC So we can wake up to the Grand Canyon if we want?

SL Absolutely with a live webcam for that matter.

MC So that means that popular photography will become more like cinematography? More experiential?

SL These portable HDTV cameras are becoming ubiquitous. Actually they’re probably on every street corner surveilling us. All you need do is go to the Google satellite to practically see yourself on camera.

MC Does this experiential future perhaps marginalize traditional print photography?

SL Well when a Van Gogh commands $20 million dollars I don’t think that printmaking is going to disappear anytime soon.

MC So the two will co-exist like digital and analog photography?

SL It’s more like rare real-estate.

MC How so?

SL Once the artist is deceased there are no more made.

MC But do I care who shoots the picture of the Grand Canyon so I can wake up to it hanging on my living room wall?

SL Well I think there is some ongoing fascination with celebrity and the people behind the camera, their life and what meaning they bring to the image. In fact, there is more obsession with celebrity today than ever before. And maybe it is a diversion from politics and sad situation — I don’t know why, but the people behind the image are even more important than the image itself.

MC Can a photographer who doesn’t follow the path of celebrity get recognized in today’s society? In other words, does work stand on its own, or is that no longer true?

SL I don’t think work ever stood on its own. I think it has always been about celebrity and probably will always be the case. That’s why I feel inadequate as an artist. The idea of being celebrated on some level is offensive, as if there is some kind of hierarchy...

MC ...of marketing, sales, PR. A machine in other words?

SL Yes

MC Is it true then that all the famous photographers today are successful celebrities?

SL Well Cindy Sherman comes to mind. Where she has celebrated herself in the image. So she’s a literal example of this phenomenon. And the fact that Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie could command 4 million dollars for the photographs of their newborn baby.

MC Does that feed our cultural narcissism?

SL I think it is a diversionary tactic on the part of the media to take its eyes off of what is really important.

MC So it would be similar to what Marx said about religion being an opiate of the people?

SL Yes. Absolutely

MC Is there room then for a true artist?

SL There is plenty of room. It just doesn’t make the headlines because it would not be cost-effective for corporations.

MC So it is the quiet determined artist doing his or her thing for themselves and there is enough ability if you are good to make a modest living but not get worldwide or even national recognition that would come only with promoting oneself.

SL I think the Internet has changed the marketplace. I grew up with ABC, NBC and CBS and now there are thousands of channels and media has decentralized and become more personalized such that one can be celebrated in microcosm.

MC Everybody can be famous for 15 minutes! But it may be that only a small bunch of people know who you are...

SL The population is so huge that a microcosm today was a macrocosm not so long ago. “Oh, you are only seen by 200,000 people” is a bad Nielsen rating.

MC Which galleries carry your work?

SL I’m carried by The Watkins Gallery locally. That’s currently my only dealer.

MC What is your relationship with your gallery? Is it a love/hate thing? Is it a totally good experience?

SL It is a great experience. I show not only in that gallery but in other places and being able to display the large format prints is critical as the internet, at six or seven inches, doesn’t really begin to tell the story like experiencing work in person. Particularly with these wide format prints, you can’t really appreciate the detail and color unless you can see them face to face. So the gallery enables one to experience what I can envision the art looking like

MC What is the biggest print you currently make?

SL 44” x 78”

MC I assume you don’t make too many of those! That is awfully big to handle!

SL No. But I have a fairly good market for my large format prints. Through my internet sales. The internet is my primary dealer/gallery. And I take out full-page ads in Art News and Art in America and that drives people to my website and those clients are willing to invest in these prints sight unseen. Which is amazing.

MC Well you have the CV to allow one to pull that off.

SL It doesn’t hurt.

You can see more of Shelley's work at www.shelleylake.com![]()

Friday, September 26, 2008

Interview: Shelley Lake

Posted by

J Michael Sullivan

at

8:13 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: INTERVIEW

Thursday, September 25, 2008

Portfolio: Diana Bloomfield

By Diana Bloomfield My very first photography class, back in 1981, was titled “Large-Format Photography,” offered at Bucks County Community College, in Newtown, Pennsylvania. At the time, I didn’t have a clue what “large-format” meant, but going on the bigger-is-better theory, I immediately registered for it. Knowing as little as I did actually turned out to be a good thing. I wasn’t yet wedded to any one type of camera, nor was I restricted in my views of how I “should” be photographing. And, fortunately, no one had ever said to me, “You can’t work with a large format camera until you master the 35mm, followed by the medium format, followed by years of darkroom work,” comments I’ve since heard over the years, from both fellow photographers and instructors. In fact, I knew so little about photography, that composing an image upside down on the ground glass seemed like the most natural exercise in the world.

My very first photography class, back in 1981, was titled “Large-Format Photography,” offered at Bucks County Community College, in Newtown, Pennsylvania. At the time, I didn’t have a clue what “large-format” meant, but going on the bigger-is-better theory, I immediately registered for it. Knowing as little as I did actually turned out to be a good thing. I wasn’t yet wedded to any one type of camera, nor was I restricted in my views of how I “should” be photographing. And, fortunately, no one had ever said to me, “You can’t work with a large format camera until you master the 35mm, followed by the medium format, followed by years of darkroom work,” comments I’ve since heard over the years, from both fellow photographers and instructors. In fact, I knew so little about photography, that composing an image upside down on the ground glass seemed like the most natural exercise in the world.

Working with a large-format camera taught me all I needed to know about light, exposure, and composition. Since I also wasn’t that accustomed to the relative ease and spontaneity that is inherent with a 35mm camera, I never felt I was giving up anything with large-format, which definitely taught me to wait, to be selective, and to take my time before clicking that shutter. Many years after that first class, I began to create images using lensless cameras and printing in “alternative” processes. These images seemed to stem more from my mind’s eye, rather than from any literal perspective. Around that same time, I had also begun teaching photography workshops myself. Long before the proliferation of digital, students would come into class with very expensive and complex cameras — all-automatic 35mm cameras — that completely overwhelmed them. They would talk about how the camera wouldn’t “allow” them to do something as simple as change aperture or shutter speed, and were totally dependent on the camera’s controls and programs. The very idea of photographing in “manual mode” threw them completely off-kilter. So I initially began to make pinhole cameras, simply to illustrate just how basic a camera really is, and that compelling images can be made with a $5 camera made out of foam core and totally lacking in programs, controls, or even a lens. I was finally able to convince them that they were in control of their cameras, not the other way around. I also showed a wide range of amazing work, made by various pinhole photographers, and, somewhere along the way, I became intrigued myself.

Many years after that first class, I began to create images using lensless cameras and printing in “alternative” processes. These images seemed to stem more from my mind’s eye, rather than from any literal perspective. Around that same time, I had also begun teaching photography workshops myself. Long before the proliferation of digital, students would come into class with very expensive and complex cameras — all-automatic 35mm cameras — that completely overwhelmed them. They would talk about how the camera wouldn’t “allow” them to do something as simple as change aperture or shutter speed, and were totally dependent on the camera’s controls and programs. The very idea of photographing in “manual mode” threw them completely off-kilter. So I initially began to make pinhole cameras, simply to illustrate just how basic a camera really is, and that compelling images can be made with a $5 camera made out of foam core and totally lacking in programs, controls, or even a lens. I was finally able to convince them that they were in control of their cameras, not the other way around. I also showed a wide range of amazing work, made by various pinhole photographers, and, somewhere along the way, I became intrigued myself. I love that the pinhole camera, with its long exposures and unique perspectives, plays with time and space in unusual ways, and offers a certain kind of fluidity not often found in still photography. And while these dreamy pinhole images might seem far removed from the early documentary work of my past, I still see similarities. For me, the attraction of photography is this idea that we can stop time and preserve it forever. Yet when I actually look at my own photographs, it’s my own memory of that time that’s been preserved, however skewed, inaccurate, and selective it is — not necessarily the actual, literal moment in time. Pinhole images, especially, seem to somehow capture our memories, transporting us to another place and time, or to a barely remembered past. They can whisk us into a future found only in the mind’s eye, and arrest the world in a timeless kind of dream. This is what I find most compelling and magical about photography — regardless of what label they’re given (documentary or otherwise). I have photographed with large-format pinhole cameras, most often home-made, including a 20x24 and a 7x17, using film of the same size. I also use an 8x10 and various 4x5 cameras. I then print in platinum/palladium, or in the dual process of cyanotype over platinum/palladium (re-registering the negative with the second process), and, more recently, gum over platinum/palladium. Since these are contact printing processes, the image is only as big as the negative; consequently, I like to start out with a reasonably large original negative, or make larger negatives digitally.

I love that the pinhole camera, with its long exposures and unique perspectives, plays with time and space in unusual ways, and offers a certain kind of fluidity not often found in still photography. And while these dreamy pinhole images might seem far removed from the early documentary work of my past, I still see similarities. For me, the attraction of photography is this idea that we can stop time and preserve it forever. Yet when I actually look at my own photographs, it’s my own memory of that time that’s been preserved, however skewed, inaccurate, and selective it is — not necessarily the actual, literal moment in time. Pinhole images, especially, seem to somehow capture our memories, transporting us to another place and time, or to a barely remembered past. They can whisk us into a future found only in the mind’s eye, and arrest the world in a timeless kind of dream. This is what I find most compelling and magical about photography — regardless of what label they’re given (documentary or otherwise). I have photographed with large-format pinhole cameras, most often home-made, including a 20x24 and a 7x17, using film of the same size. I also use an 8x10 and various 4x5 cameras. I then print in platinum/palladium, or in the dual process of cyanotype over platinum/palladium (re-registering the negative with the second process), and, more recently, gum over platinum/palladium. Since these are contact printing processes, the image is only as big as the negative; consequently, I like to start out with a reasonably large original negative, or make larger negatives digitally. So, here, in this 21st century world of digital technology, where the creation of illusion is as close as the touch of a keyboard, and where images can be infinitely reproduced with repeatable precision and accuracy, some of us are still working with relatively antiquated methods of the past, either in our choice of camera, in our printing methods, or in both. And, yet, many of us willingly turn to computer technology — in my case, as a way to create larger negatives suitable for contact printing.

So, here, in this 21st century world of digital technology, where the creation of illusion is as close as the touch of a keyboard, and where images can be infinitely reproduced with repeatable precision and accuracy, some of us are still working with relatively antiquated methods of the past, either in our choice of camera, in our printing methods, or in both. And, yet, many of us willingly turn to computer technology — in my case, as a way to create larger negatives suitable for contact printing.

For me, making digital negatives has been nothing short of a dream. If needed (often the case with original pinhole negatives), I can change or correct the density of my negatives to suit a particular alternative process or to control my exposures in printing; I can easily and seamlessly erase unavoidable scratches and dust marks; I have also recently made CMYK separation digital negatives for use in tri-color gum printing (something I have yet to master, but the capability of doing so is right there at my fingertips). Another non-trivial positive is that my original negatives can be preserved, without suffering the degradation of constant use in alternative printing. While digital transparencies are not inexpensive, knowing that I can make another if one is damaged is certainly liberating. Obviously, the possibilities with digital are limitless. While borrowing from the past, in both choice of camera and printing methods, affords limitless learning, discovery, and creative opportunities, meshing those antiquated techniques with the seemingly futuristic and ever-changing world that is digital, makes this an exciting time to be a photographer. As an old friend of mine once remarked, “19th Century craft immersed in a decidedly digital future — what a perfect art this is.”

While borrowing from the past, in both choice of camera and printing methods, affords limitless learning, discovery, and creative opportunities, meshing those antiquated techniques with the seemingly futuristic and ever-changing world that is digital, makes this an exciting time to be a photographer. As an old friend of mine once remarked, “19th Century craft immersed in a decidedly digital future — what a perfect art this is.”

Reprinted from MAGNAchrom Magazine, Vol 1, Issue 6. www.magnachrom.com

You can download the reprint of this article in PDF format here:

MAGNAchrom.v.1.6.DianaBloomfield.pdf![]()

Posted by

J Michael Sullivan

at

6:23 PM

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: ALT PROCESSES, PORTFOLIO

Tuesday, September 23, 2008

Photokina 2008 Musings

HASSELBLAD UNDER PRESSURE!

So far, one of the biggest (and frankly totally unexpected) surprises at Photokina 2008 is the announcement by Leica of a "full sized" DSLR camera body offering a unique 37.5-megapixel, 30x45mm sensor together with a complete new line of Leica lenses. This camera offers both leaf and focal-plane shutters. Curiously, it reminds me greatly of a mini-version of the classic Pentax 67! If priced well, this could bring Leica back into the game as the full-frame camera arena is getting crowded these days and there is a speed and handling weakness with current digital medium format offerings by the likes of Hasselbllad, Sinar, Mamiya, PhaseOne, and Leaf.

Clearly, the move is both defensive, in that Leica can no longer look back to those halcyon days when it commanded the premier brand, as well as offensive — specifically to Hasselblad... Consider the following points:

¶ 3 years ago, Hasselblad effectively abandoned its classic 50x architecture in favor of its newer, lighter all-digital system, much to the dismay of its diehard fans. This move eliminated an easy upgrade path to the new architecture, further isolating its user base. Lastly, Hasselblad decided on a closed system, thus forcing users to buy exclusively from Hasselblad. Apple tried this and failed. It remains to be seen if this is a smart move or not.

¶ Additionally, it also abandoned its long-standing relationship with Zeiss in favor of Fuji for its glass. While Fuji lenses are arguably "just as sharp", the Zeiss brand conveyed a prestige and guarantee of top quality. The German lens manufacturers have never forgiven them this slight. This may explain the eagerness Zeiss has shown to get into bed with Sony — to punish Hasselblad.

¶ Phase One has been a long-time competitor to Hasselblad and now they have entered into a strategic relationship with Leica to go after the pro market in a big way. So not only does Phase One have Leica now as a partner, it also has Mamiya. With these strategic alliances, Phase One can squeeze Hasselblad from both ends of the market

¶ In response, Hasselblad has recently offered its entry-level, H3DII-31 system at significant discount rates and is encouraging its resellers to offer agressive lease plans. Lowering prices is their only option at the moment since the overall quality of a Hasselblad system can be equaled by several vendors, most of which offer "open systems". My take: manufacturers lower prices this dramatically only when they plan to end-of-life their product. Expect to see the 31mp Hassy disappear from the official list of Hasselblad products within the next 3-6 months.

¶ Feeling the heat, Hasselblad has recently announced a future delivery of a larger "645" sensor which will likely be 54x40mm to match Phase One's offering. Presumably this new sensor will also require a new body (the HC4?). Further, such a bigger sensor will possibly REQUIRE the use of the special-purpose "tilt/shift" lenses (i.e. HC28, HC35, HC50, HC80, HC100) all of which have a larger image circle. It is not clear how the other current Hassy lenses would/could work with this new larger-sensor model. Changing architectures this significantly mid-stream might add to current user complaints. (unless they make it backward compatible with the 50x series!! Fat chance)

¶ Sinar in particular might be in the cat-bird seat as they stuck with maintaining compatibility with the 6x6 format in their Rollei-based, Hy6 camera system which will eventually allow them to offer 56x56mm sensors as they become available. Given the drastic drop in the cost of silicon sensors, I wouldn't be surprised to see a 6x6 sensor within two years. Such a sensor could relegate Hasselblad to "me too" status among medium format manufacturers. (of course, they could always resurect their 50x series! Wouldn't that be ironic!)

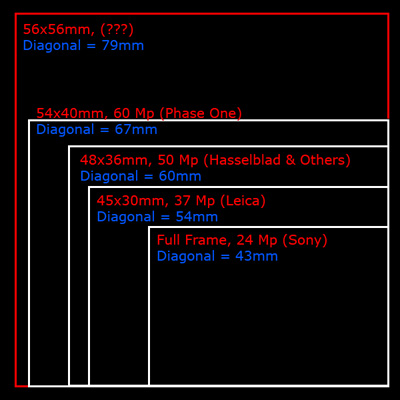

As you can see from the above diagram, Hasselblad's bet on the 36x48mm standard has suddenly become a VERY crowded place with competitors at every turn. It remains to be seen if Hasselblad can survive. Personally I hope so as I admire their products and vision.

What are your thoughts?![]()

Posted by

J Michael Sullivan

at

7:43 AM

2

comments

![]()

![]()

Sunday, September 14, 2008

Modifying a Mamiya Tele-Converter 1.4xRZ to fit an RB67

By J Michael Sullivan

We RB67 owners are second-class citizens when it comes to comparing our beloved beast of a camera to its electronic brother the RZ67. Perhaps one of the most obvious examples is that Mamiya never offered a 1.4x teleconverter for the RB67 — something in my opinion is a glaring omission. Fortunately, the RZ67 and RB67 share the same mounting ring. I wondered: could I modify the RZ67 teleconverter to work with an RB67? I figured I'd give it a try.

First thing was to procure a Mamiya 1.4x tele-converter. Lucky for me there was one in exc+ condition on eBay that with some counter-bidding I was able to purchase for only $142. Upon inspecting it, it was clear that the primary problem with mounting it to the RB67 was two obnoxious studs that got in the way of the tele-converter from being mounted properly on the otherwise identical RB67 lens mount. Amazingly, I could find NOTHING on the internet regarding whether these two studs had any purpose other than preventing RZ lenses from mounting on RB bodies. I decided that they must serve no other purpose and herein document the steps I took to modify the 1.4x tele-converter for use with my RB67.

Equipment needed:

- a small "jewelers" philips screw driver

- a 1/16" drill

Estimated time:

- 5 minutes

STEP 1: Note the two offending studs — these prevent RZ lenses from being mounted onto an RB body.

STEP 2: Remove the plate by unscrewing the 4 mounting screws with your jeweler's philips screwdriver. Be careful not to lose the Shutter Release Lock Pin (see previous image).

STEP 3: Flip the plate over and using the 1/16" drill, drill out the soft bronze studs BY HAND (do not use a power drill).

STEP 4: Dust it off, and align it back on the teleconverter, being sure to locate the Shutter Release Lock Pin back in its proper location. Re-attach the 4 mounting screws

STEP 5: Verify that you can manually move the shutter cocking pins

STEP 6: Mount the teleconverter on your RB67

STEP 7: Mount your lens on the teleconverter (Note: the teleconverter is optimized for 90mm to 180mm lenses)

STEP 8: Verify that you can cock the shutter

STEP 9: Take your picture! (Note that you will need to add exactly 1 stop more exposure to compensate for the 1.4x longer lens)

And that's about it. Here is a sample photo using a Mamiya RB67 + 250mm + 1.4x teleconverter:

Posted by

J Michael Sullivan

at

3:15 PM

4

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: HOT MODS, MEDIUM FORMAT

Saturday, September 13, 2008

Working Class

The 8x10 photographs of Cristina Mian & Marco Frigerio

By CRISTINA MIAN e MARCO FRIGERIO Working Class is a part of our series about the consequences for Italy’s economic structure since China was accepted into the WTO. Many Italian factories, especially in the textile sector, are rapidly transferring their production to the Chinese, resulting in massive economic changes to both the landscape as well as workers.

Working Class is a part of our series about the consequences for Italy’s economic structure since China was accepted into the WTO. Many Italian factories, especially in the textile sector, are rapidly transferring their production to the Chinese, resulting in massive economic changes to both the landscape as well as workers.

The body of work is currently composed of four chapters: Invisible workers, Ideographs, The Dragon invasion, and Working Class. But Working class in particular represented for us a way for exploring new photographic territories and expanding the boundaries of our way of composing and thinking of our photography. In fact for the very first time we decided to put ourselves into the frame, to become part of the composition, and to use our presence, our body, as a form of interaction with the ambience we were capturing. For the other chapters in our series, we’ve always photographed in a Dusseldorf school-like way — very objective and very depictic. However, at a certain point in researching Working Class, we realized that this was not sufficient anymore, as we felt the need of a more subjective point-of-view: A photography in which not only our thoughts, our emotions, our visions, were clearly expressed, but in which we had the possibility to “risk” ourselves. We wanted to be modified by what we felt and saw in the places we were in. To experience directly the feel on our skin, the smells, the memories, the emotions, and the lives connected with those places.

For the other chapters in our series, we’ve always photographed in a Dusseldorf school-like way — very objective and very depictic. However, at a certain point in researching Working Class, we realized that this was not sufficient anymore, as we felt the need of a more subjective point-of-view: A photography in which not only our thoughts, our emotions, our visions, were clearly expressed, but in which we had the possibility to “risk” ourselves. We wanted to be modified by what we felt and saw in the places we were in. To experience directly the feel on our skin, the smells, the memories, the emotions, and the lives connected with those places.

We also wanted to experiment with our bodies, in one world to interact with our subjects in a way that this interaction became for us —both on a personal as well as on a photographic level — a means of continuous personal discovery, pushing our research into unexpected and unknown territories. This is why we decided to put ourselves in our Working Class images. And our interest for performance art and body art played an important role, since we became interested in these artistic disciplines it was clear for us that we had the expressive need to “translate” their influences in our photography. In other words, they had to be part of our creative processes. From a visual point of view we were influenced by our devoted passion for Francis Bacon’s paintings. In many of his works, particularly around the main contorted figure(s), there are often other figures that he called “Observers” or “Witnesses” (for example, a man with a hat, or a photographer, or whatever). This kind of visual and conceptual reference deeply influenced the way we posed or acted inside our composition. For example, the way we manipulated or used some objects (like a newspaper). That is not to say that everything was planned. On the contrary, improvisation was our way of choosing how to pose and what to do. But it was a kind of improvisation deeply informed by the influences from performing art, body art and Bacon, and that which we had “accumulated” over the years. And it was this rich history which at that in that particular moment exploded in a new and more personal form.

From a visual point of view we were influenced by our devoted passion for Francis Bacon’s paintings. In many of his works, particularly around the main contorted figure(s), there are often other figures that he called “Observers” or “Witnesses” (for example, a man with a hat, or a photographer, or whatever). This kind of visual and conceptual reference deeply influenced the way we posed or acted inside our composition. For example, the way we manipulated or used some objects (like a newspaper). That is not to say that everything was planned. On the contrary, improvisation was our way of choosing how to pose and what to do. But it was a kind of improvisation deeply informed by the influences from performing art, body art and Bacon, and that which we had “accumulated” over the years. And it was this rich history which at that in that particular moment exploded in a new and more personal form. We prefer that everyone viewing these photographs find his/her own personal meaning for the “disappearing” figures. Our original intention was that they symbolize the fact that we are “crossed” by those places, but also that we were passing through them, like a kind of mutual absorption in a mutual modification/interaction. We also liked the fact that those disappearing figures are as if they were coming from nowhere, past or present or future, and going nowhere, or just disappearing into those places, into memories, into the glass and steel...

We prefer that everyone viewing these photographs find his/her own personal meaning for the “disappearing” figures. Our original intention was that they symbolize the fact that we are “crossed” by those places, but also that we were passing through them, like a kind of mutual absorption in a mutual modification/interaction. We also liked the fact that those disappearing figures are as if they were coming from nowhere, past or present or future, and going nowhere, or just disappearing into those places, into memories, into the glass and steel...

Cristina is not present in any of the photos as at the time she was pregnant, and it seemed to us much too “obvious” to portray a pregnant woman, as there are too many strict meanings connected with maternity and birth.

You can see more of Marco & Christina’s work by visiting their website: www.cristinamian.com.

From a technical point of view, all the “Working class” series was photographed with an 8x10 view camera (either Calumet C1 Green Monster or Sinar F2), using Velvia 50 and Velvia 100F transparency film.

Reprinted from MAGNAchrom Magazine, Vol 1, Issue 4. www.magnachrom.com

You can download the entire PDF here:

MAGNAchrom.v.1.4.1.Marco_Cristina.pdf![]()

Posted by

J Michael Sullivan

at

9:39 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: LARGE FORMAT, PORTFOLIO

Tuesday, September 9, 2008

News: Kodak Ektar 100

Kodak continues its commitment to film. On September 9th 2008, they announced a new, ISO 100, 35mm color negative film, Kodak Professional Ektar 100. According to Kodak, Ektar 100 “offers the finest, smoothest grain of any color negative film available today.”

Kodak continues its commitment to film. On September 9th 2008, they announced a new, ISO 100, 35mm color negative film, Kodak Professional Ektar 100. According to Kodak, Ektar 100 “offers the finest, smoothest grain of any color negative film available today.”

They tout that it is ideal for scanning. Obviously, this good news for those who continue to shoot film. It will be interesting to compare its quality to that of the newer breed of digital SLRs. One could expect it to provide similar quality to even the most expensive DSLRs as much of the resolution of a system is dependent upon the lens anyway.

With such a high-quality product, one can only hope that Kodak will release roll film as well as sheet film versions in the near future!

Learn more about Kodak Professional Ektar 100 35mm color film click here.

NOTE: if you want your product reviewed or announced on this blog, please send email to editor "at" magnachrom "dot" com Read More...

Posted by

J Michael Sullivan

at

12:33 PM

3

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: NEWS

Sunday, September 7, 2008

eBay Bargain: RB67 Pro SD

It is amazing to me some of the things that slip by on eBay (on the other hand, it is equally amazing to me how people regularly overpay on eBay as well).

Here is one that I thought was deserving: An exc+ Mamiya RB67 Pro SD body for a "buy it now" price of just $219.95! No takers! What's the world coming to?

P.S. Shutterblade reposted the item a few weeks later and someone did indeed snatch it up.

P.P.S. I've purchased many things from Shutterblade and find them to be a reasonable source. Just be sure to ask lots of questions! See their ShutterbladeStore

NOTE: if you know of any noteworthy eBay listings for medium or large format equipment, please send email to editor "at" magnachrom "dot" com. Thanx!

Posted by

J Michael Sullivan

at

9:08 AM

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: EBAY OBSERVATIONS

Saturday, September 6, 2008

Review: VisibleDust™

By Joan Sullivan

Joan has spent the majority of the past 20 years living/working in and otherwise roaming around Africa and Asia. When she is not designing HIV prevention and behavior change interventions, she is behind a camera. Digital photography lends itself well to such a mobile lifestyle; it is now her preferred medium. In the War On Dust, we are all reluctant conscripts. Sooner or later, no matter what digital format we’re shooting, no matter how meticulous we are when changing lens, no matter how good our Photoshop skills, we will be forced to choose a weapon and do the unthinkable — clean the sensor.

In the War On Dust, we are all reluctant conscripts. Sooner or later, no matter what digital format we’re shooting, no matter how meticulous we are when changing lens, no matter how good our Photoshop skills, we will be forced to choose a weapon and do the unthinkable — clean the sensor.

The good news is that ‘sensor cleaning’ is a misnomer. The hermetically sealed image sensor lies protected behind a low pass filter, so we — and the ubiquitous dust — do not have easy access to it, for good reason. Instead, what we touch during the sensor cleaning process is the low pass filter, not the actual CCD or CMOS.

The bad news is that this silica filter is highly sensitive and can be easily scratched if proper cleaning techniques are not meticulously observed. You could also cause serious damage should the battery suddenly die during cleaning, causing the mirror lock-up mechanism and shutter to release while you are inside the camera chamber. The same risk applies if, for some reason, you use bulb setting while cleaning. Thus, be forewarned [Praemonitus praemunitus]: to minimize risk while cleaning the sensor and/or camera chamber, always place your camera in ‘sensor cleaning’ mode while your camera is hooked up to AC power. If this is not possible, then only a fully-charged battery should be considered as a last resort.

So which cleaning weapon to use?

There is a small but growing arsenal of sensor cleaning methods. These fall primarily into two camps: “wet” and “dry”. Other high tech strategies, such as the new self-cleaning sensor units from Canon and Nikon and built-in dust removal software to delete residual dust spots from processed images, will not be discussed here.

For this review, we tested three VisibleDust products that were received unsolicited from the Canadian manufacturer. These include the VisibleDust DHAP Sensor Cleaning Swab™ (for wet cleaning), the VisibleDust Arctic Butterfly® 724 Sensor Brush (for dry cleaning), and the VisibleDust Sensor Loupe™. All products were tested on an old Canon 20D with plenty of accumulated dust. Before discussing the wet and dry methods, we’d like to say right up front that we were very impressed with VisibleDust’s sensor loupe. Although there are other less expensive tools to examine camera interiors, we found that the array of six LEDs inserted into the circular interior wall of this loupe provide superb lighting which evenly fills the chamber to improve detection of dust and other debris on the sensor filter as well as within the chamber.

Before discussing the wet and dry methods, we’d like to say right up front that we were very impressed with VisibleDust’s sensor loupe. Although there are other less expensive tools to examine camera interiors, we found that the array of six LEDs inserted into the circular interior wall of this loupe provide superb lighting which evenly fills the chamber to improve detection of dust and other debris on the sensor filter as well as within the chamber.  In our opinion, the most important use of this kind of sensor loupe is to help the photographer determine, a priori, what cleaning method is most appropriate for each cleaning session in order to minimize physical contact with the sensor filter. If you see through the sensor loupe that most of the dust is only loosely attached to the sensor filter, then you should start with a dry method such as blowing air (not compressed air!) or the VisibleDust Arctic Butterfly described below, since dry methods are less invasive than wet methods. However, if you see spots on the sensor filter through the sensor loupe, then you will have to use a wet cleaning method which requires physically wiping the sensor filter.

In our opinion, the most important use of this kind of sensor loupe is to help the photographer determine, a priori, what cleaning method is most appropriate for each cleaning session in order to minimize physical contact with the sensor filter. If you see through the sensor loupe that most of the dust is only loosely attached to the sensor filter, then you should start with a dry method such as blowing air (not compressed air!) or the VisibleDust Arctic Butterfly described below, since dry methods are less invasive than wet methods. However, if you see spots on the sensor filter through the sensor loupe, then you will have to use a wet cleaning method which requires physically wiping the sensor filter.

The sensor loupe also comes in handy after cleaning, to examine the sensor before re-attaching the lens or lens cap. In particular, it can help highlight any stubborn particles or spots which prove resistant to your best cleaning efforts.  Using the VisibleDust sensor loupe, we examined the camera chamber of the Canon 20D and determined that most of the dust particles were loosely attached to the sensor filter. VisibleDust’s Arctic Butterfly 724 Sensor Brush is one of several types of dry sensor cleaning products on the market, but it stands out with its patented super-charged fiber technology (SFT). It combines a 16mm sensor brush, a rotating DC motor and two AAA batteries in a plastic housing. By pushing a button on the handle for about 10 seconds -- away from the camera, prior to inserting it into the camera chamber — the head spins rapidly to charge the bristles. These positively charged bristles attract dust, and when drawn gently a few times across the sensor filter, they literally lift dust right off the sensor filter. Pull the Arctic Butterfly out of the camera, spin again to dislodge any dust picked up by the bristles and put the cover back on to protect the bristles. It is very easy to use, and

Using the VisibleDust sensor loupe, we examined the camera chamber of the Canon 20D and determined that most of the dust particles were loosely attached to the sensor filter. VisibleDust’s Arctic Butterfly 724 Sensor Brush is one of several types of dry sensor cleaning products on the market, but it stands out with its patented super-charged fiber technology (SFT). It combines a 16mm sensor brush, a rotating DC motor and two AAA batteries in a plastic housing. By pushing a button on the handle for about 10 seconds -- away from the camera, prior to inserting it into the camera chamber — the head spins rapidly to charge the bristles. These positively charged bristles attract dust, and when drawn gently a few times across the sensor filter, they literally lift dust right off the sensor filter. Pull the Arctic Butterfly out of the camera, spin again to dislodge any dust picked up by the bristles and put the cover back on to protect the bristles. It is very easy to use, and  After using the Arctic Butterfly, we re-examined the sensor filter with the sensor loupe, and concluded that 95% of the dust particles had been successfully removed. However, we could still see one rather large dust particle on the filter.

After using the Arctic Butterfly, we re-examined the sensor filter with the sensor loupe, and concluded that 95% of the dust particles had been successfully removed. However, we could still see one rather large dust particle on the filter.

To remove it, we next used VisibleDust’s DHAP Sensor Cleaning Swab with three drops of VDUST PLUS Liquid as per instructions. After one swipe with the orange cleaning swab, we re-examined the filter with the sensor loupe and saw a perfectly clean filter. What a beautiful sight! Could we have arrived at the same result using just the wet swab without having first used the Arctic Butterfly? Perhaps, but there is something infinitely logical to trying to remove as much dust and debris as possible prior before physically dragging a swab over the sensor filter. For this reason alone, we would still recommend that your sensor cleaning strategy begin with a quick swipe of the Arctic Butterfly, followed by a quick swipe of a moist swab. However, if you are in a particular hurry and can’t do both, then you will probably get similar results from just the wet cleaning method, which we have been using successfully for several years.

Could we have arrived at the same result using just the wet swab without having first used the Arctic Butterfly? Perhaps, but there is something infinitely logical to trying to remove as much dust and debris as possible prior before physically dragging a swab over the sensor filter. For this reason alone, we would still recommend that your sensor cleaning strategy begin with a quick swipe of the Arctic Butterfly, followed by a quick swipe of a moist swab. However, if you are in a particular hurry and can’t do both, then you will probably get similar results from just the wet cleaning method, which we have been using successfully for several years.  Whatever your sensor cleaning strategy, don’t forget to clean the lens mount and rear element before re-attaching the lens to the body. Furthermore, since the mirror stirs up a lot of dust inside the camera chamber every time you take a picture, it makes good sense to keeping the walls of your chamber as clean as possible as well, especially if working in a particularly dusty environment and if you change lenses frequently. And, on a final note, we have heard from several photographers that storing cameras face down in camera bags with lenses attached also can minimize dust from entering the chamber.

Whatever your sensor cleaning strategy, don’t forget to clean the lens mount and rear element before re-attaching the lens to the body. Furthermore, since the mirror stirs up a lot of dust inside the camera chamber every time you take a picture, it makes good sense to keeping the walls of your chamber as clean as possible as well, especially if working in a particularly dusty environment and if you change lenses frequently. And, on a final note, we have heard from several photographers that storing cameras face down in camera bags with lenses attached also can minimize dust from entering the chamber.

In conclusion, we believe that no one cleaning method will work for all photographers with all cameras in all situations. The rule of thumb is not to be obsessive about keeping your sensor clean, and not to clean the sensor any more frequently than absolutely necessary.

You can see Joan's work at www.joansullivanphotography.com![]()

Posted by

J Michael Sullivan

at

3:52 PM

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: REVIEW